Asian hornet – Vespa velutina

The Asian hornet is an alien species that has entered the UK on several occasions and represents a threat to honeybees.

Your committee takes the view that ALL members should acquaint themselves with the risks and possible dangers posed by Asian hornets as well as the way forward if we are invaded.

Check out the BBKA Asian hornet page to help the fight against the Asian hornet invasion.

Three things to do if you think you have Asian hornets near your bees.

- Check the identification is correct.

Use the images and notes below. If you need help then call your nearest swarm collector who is prepared to help with this task. - Obtain a sample.

A child’s shrimping net or hornet trap can be used. - Send the dead sample to the National Bee Unit.

Address: National Bee Unit, The Animal and Plant Health Agency, Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ

The NBU will not act until they have identified the sample so it is important to act quickly.

The following information covers identification, what to do in the event of invasion, background information and links to useful sites.

Identification

These images show the essential features for identification. The most likely mis-identification is with Vespa crabro, our European hornet.

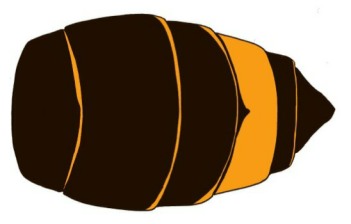

Asian hornet

Note the yellow legs and the single broad yellow band near the tail.*

Asian hornet

The features shown will easily distinguish the Asian from the European hornet.*

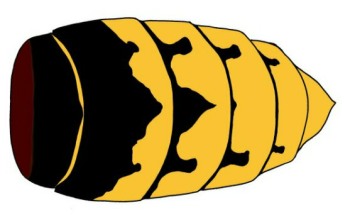

European hornet

Vespa crabro. Distinctive yellow abdomen.*

Asian hornet abdomen

Note the broad yellow band near the tail.

European hornet abdomen

The European hornet is slightly longer than the Asian hornet.

Wasps

Wasps have similar yellow and black markings to the European hornet.

Beewolf

This beewolf is carrying honeybee prey. Abdomen yellower than Asian hornet.

Asian hornet on ivy

*Images courtesy The Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), Crown Copyright

Essential reading for identification.

Asian hornet poster issued by the GB non-native species secretarial (NNSS).

Asian hornet alert, also issued by NNSS.

What to do in the event of invasion.

When a positive identification of Asian hornet has been made it is essential to notify the Great British Non Native Species Secretariat (NNSS) immediately. In the first instance their online notification form should be your first port of call by supplying a photo if possible.

You could also send an alert email to alertnonnative@ceh.ac.uk

If you have an iPhone or Android, download the free recording app: Asian Hornet Watch which allows you to take photos and submit the location of your siting using GPS.

Background information and links to helpful sites

Understanding the life cycle of the Asian hornet is essential for our eventual control of this predator. A brief guide is given after this section.

The GB non-native species secretariat website has a species information sheet specifically for the Asian hornet.

The Devon Beekeepers’ Association website has information on identification, obtaining a sample, Guidance Protocols for beekeepers and branches plus all the links for sample submission.

The Asian Hornet Action Team website, run by Devon Beekeepers, has articles on identification, sample collection, the Jersey Method of tracking nests and the latest information concerning anti-trapping.

Life Cycle

Professor Stephen Martin at University of Salford has recently published a book called The Asian Hornet – Threats, Biology & Expansion. Here are some of the observations of an expert who has been studying hornets since 1987.

The life cycle is similar to wasps and bumble bees. Queen hornets mate in the autumn and hibernate in a safe niche protected from rain, snow and wind. During hibernation queens fold their wings under their abdomen, pressed against their body, giving them a distinctive appearance. The queens will come out of hibernation as the weather warms.

The queen’s fat reserves will be low so she seeks nectar and tree resin to activate her ovaries and sustain nest building activities. During the next few weeks she hunts for a suitable nest site, usually enclosed and protected, then begins the building process using wood fibres. The nest hangs down and is attached to the substrate at the top by a stalk or petiole. The lower end of the stalk forms the hexagonal cells for brood rearing. They hang down with the open end at the bottom. The entire structure is surrounded by a thin wood fibre (paper) envelope and at this stage may be 4 -5cm across.

Beginning of proto-nest

Beginning of proto-nest

Proto-nest

Proto-nest

Secondary nest

Secondary nest

All images Courtesy The Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), Crown Copyright

When this proto-nest is finished the queen lays an egg at the base of each cell attached to the cell wall by an adhesive. Hatching in 3 to 4 days the larva initially remains attached to the old egg case to prevent falling out of the cell. Eventually the larva grows big enough to fill the whole cell, spins a silken cocoon and pupates. It takes about 50 days for the lone queen to build the proto-nest and at this stage the time from egg to adult worker may take 50 days as the nest is too small to thermoregulate.

When the first workers appear there is a short ‘co-operative’ period around June when both workers and queen are active outside the nest. As the colony numbers increase, the queen stays in the nest and becomes the egg layer.

June to August sees rapid expansion in nest size and colony numbers and if the original location is too small the whole colony may re-locate to a more suitable site, in a tree or under the eaves of a tall building. This process may only take a few days.

During the ‘reproductive phase’ (September to October) the nest is large enough to thermoregulate at around 30°C and the time from egg to adult reduces to 29 days. Some larger cells will be created for the queen to lay unfertilised eggs that will become drones and fertilised eggs that will be queens. Numbers of queen and drone hornet produced vary considerably, largely dependent on climatic conditions. 300 queens and 600 drones are possible but with favourable conditions these numbers could treble!

These ‘sexuals’ stay in the nest for a week or so building up their fat reserves then leave the nest without an orienting flight as they will not return. After mating, the fertilised queen seeks a safe place to hibernate, the drones die and the nest goes into decline. The whole Asian hornet cycle takes 8 – 10 months compared to 5 -6 months for the European hornet.

How to protect your bees

Professor Martin argues that the only proven method of hornet control is colony discovery and destruction. Neither task is easy. The advice given in the book is to call in the professionals! Never attempt to remove or kill an Asian hornet nest yourself. If things go wrong you put yourself and others in grave danger, even of being killed as has happened in France. We have a long way to go before an effective strategy emerges to protect our bees and the public from this very successful alien species.

See the Library page for details of:

The Asian Hornet – Threats, Biology & Expansion by Dr Stephen Martin.

The Asian Hornet Handbook by Dr Sarah Bunker of Okehampton branch.