The Honey Bee Microbiome – An adventure on the inside

A talk by Graham Kingham to East Devon Beekeepers, 5/10/23

‘You are what you eat’ or more correctly, what you digest. We will briefly look at human and honey bee digestion and the alimentary canal. The honey bee microbiome will be explained and the effects of disease, pathogens and chemicals mentioned.

Definition

The microbiome is the collection of all microbes, such as bacteria, fungi and viruses, and their genes, that naturally live on the outside and inside of bodies.

Microbes are very small but can contribute in a big way to the health and wellbeing of a human or a bee. They protect against pathogens, help the immune system develop, and enable digestion of food for energy production. Most microbes are harmless but nearly all life, including plants, cannot live without them. The human microbiome is composed of communities of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and parasites that have greater complexity than the human genome itself.

Microbiome research is a relatively recent topic, with the human microbiome taking centre stage. Often-quoted numbers for human microbiome are 100 trillion microbes per person, 95% of all human microbiota is in the gut, the microbiome weighs 2kg, 90% of disease can be linked in some way to the gut and microbiome health. There are hundreds of different species of microbe in the human gut.

Every part of an animal has a microbiome e.g., skin, urogenital tract, mouth and digestive tract. All these sites, microbes and inter-relationships make the microbiome extremely complicated to research and understand.

The role of the human microbiome

The human microbiome has extensive functions such as the development of immunity, defence against pathogens, host nutrition including the production of short-chain fatty acids important in host energy metabolism, synthesis of vitamins and fat storage. It has an influence on human behaviour, making it an essential organ of the body without which we would not function correctly. The human microbiome tends to be dynamic and variable dependent on many factors, including food, environment and medication.

The honey bee gut and microbiome

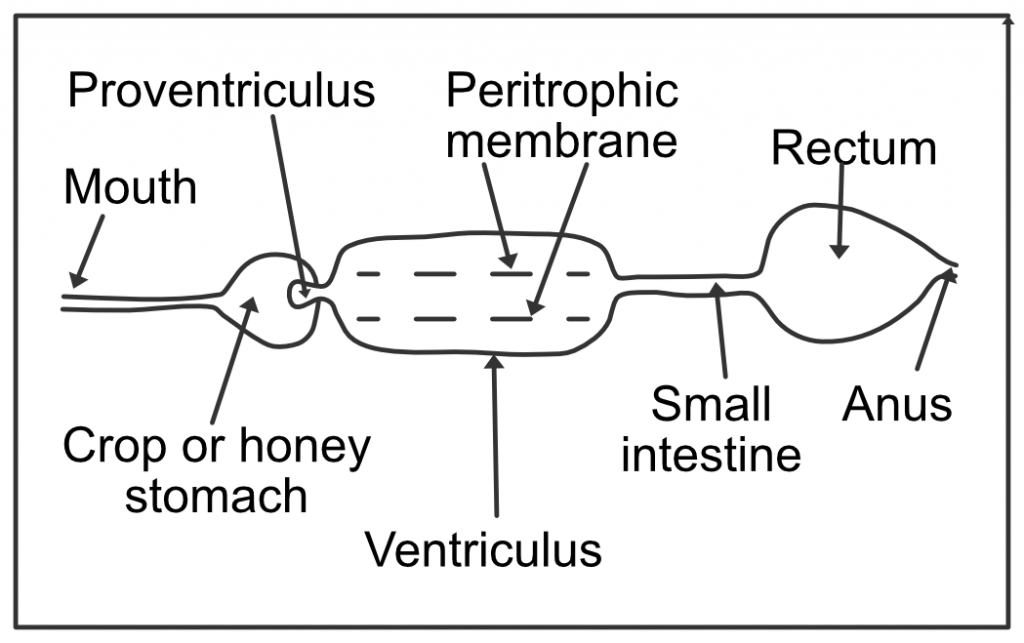

Bees have a less variable diet compared to humans with only 5-9 species dominating the gut microbiome. The bee gut consists of a tube from the mouth to the anus with specialised regions along its length performing distinct tasks (see References).

The crop

The crop or honey stomach receives the nectar/pollen mix during foraging. Also in the same region is the proventriculus or stomach mouth, a projection into the crop from the ventriculus or stomach. This valve prevents the collected honey from running into the stomach but allows the pollen to pass. Crop microbiome is mainly derived from the surrounding environment and tends to be variable with seasonally changing diets.

Ventriculus

This is a long, wide tube lined with a membrane (the peritrophic membrane) which is continually in a state of proliferation. Muscle fibres force the gut contents towards the rear and the membrane is detached and mingles with the food. The membrane produces enzyme secretions which aid the digestion of the protein contained in the pollen grains. The microbiome at this stage can still be variable depending on the environment.

The peritrophic membrane was thought to protect the lining of the ventriculus from sharp, spiky pollen grains but is now considered to be important in concentrating a range of digestive enzymes where they are most needed.

Small intestine

This is a narrow tube which is surrounded with the outlets of the Malpighian tubules. These tubules act in a similar way to the human kidney. The tubules are followed by the pyloric valve which controls the flow of material along the intestine.

Rectum

The small intestine opens into the rectum, which is capable of great distension to accommodate the waste material during long periods of confinement. The vast majority of the bacterial community live in this region as it is more stable.

The relative simplicity of the honey bee microbiome leads to a very consistent set of bacterial species known as core bacteria. These are present in all honey bee workers worldwide. Understanding how the microbiota interacts as a community helps predict how that community will react to change and how that change will affect the host.

Larvae and newly emerged bees have little bacterial colonisation. Cell cleaning provides a faecal origin for the initial inoculation. Thereafter, the microbiome will adapt to diet and environmental conditions. In a relatively constant colony, the core microbiota is maintained. Over time, as colonies split, some microbes may evolve to improve the survival of the colony, thus ensuring their own survival.

What effect does the beekeeper have on the microbiome?

- Feeding liquid sugar syrup or fondant can lead to blistering in the ventriculus.

- Food supplements such as pollen substitutes are not normally consumed by bees in their natural environment, so must have an effect on their microbiome.

- Smoking bees and weekly inspections disturb and stress the colony, with loss of pheromones for possibly several days.

- Varroa treatments and pesticides linger in wax for a long time. They have been shown to affect bee systems, such as the fertility of drones, but currently their effects on the bee microbiome have not been published.

- Thymol additives to stop mould growth or treat Varroa can repel bees. The odour can mask the chemical cues that trigger the removal of diseased or dead brood thereby affecting hygienic behaviour. As a mould inhibitor, thymol must affect the microbiome.

Treating bees is a trade-off between starvation, disease and pest control.

What can we do?

We can be more proactive in helping bees. Bear in mind that they have survived for millions of years without our help!

- Try to leave honey on the hive for winter feed. This is the best food for bees.

- Consider the forage in your area, and whether you could move your colonies to an area with better forage. Can the forage in your area support the number of colonies in your apiary?

- Practice good husbandry. Reduce stress of your bees wherever possible as stress adversely affects the microbiome.

- Always practice good hygiene.

- Consider your Varroa treatment. Is there a ‘kinder’ option?

- Work towards becoming treatment-free.

- Handle bees gently and use minimal smoke.

References

These references to honeybee anatomy are both available in the East Devon branch library.

H A Dade – Anatomy and Dissection of the Honeybee. International Bee Research Association.

Celia F Davis – The Honeybee Inside Out. Bee Craft Ltd.