How to Keep Calm and Carry on

A talk by Clare Densley and Martin Hann at Kilmington Village Hall, 1st February 2024.

A joint meeting with West Dorset branch. 60+ attendees.

Richard Simpson welcomed back Clare and Martin. The full title is How to Keep Calm and Carry on when Things Don’t Go as Planned (with your Bees). The talk will look at three topics:

– Dead outs (bees died during the winter),

– My colony does not have a queen,

– I have too many colonies.

Dead Outs

‘My bees all died, and I don’t know why’ is the question we need to answer. It will probably be one of the following:

- Starvation, including isolation starvation

- Queen failure

- Vairimorpha (Nosema) or other disease

- Varroa

- So called Acts of God e.g., the hive blows over

Starvation

Colony probably died of starvation

Dead bees in cells

Starvation can usually be identified by the appearance of the comb. The images show the typical appearance of starvation, the bees having their heads in the comb, trying to reach the last vestige of honey. If there is plenty of honey further away from the cluster then it is probably an isolation starvation situation which occurs when the bees cannot leave the cluster during a cold spell.

This raises lots of questions:

How much food does the colony need to overwinter? Do small colonies need less? What kind of food/stores? When should I feed my bees? Does it matter where it is stored?

Martin suggested a full super of stores, 35-40 lbs, should be adequate provided the bees have access, (no queen excluder in the way), and can move up through the stores during the winter. They need to stay in easy reach of stores at all times. Do not feed syrup after the ivy crop has finished. It is too damp and cold for the bees to store as honey. If more stores are needed later than this then feed fondant. Remember, bees need water to utilise ivy honey and fondant.

Queen failure

Comb of drone laying queen *

Multiple eggs of laying workers in each cell

The image above shows the typical comb of a drone laying queen. When this occurs during autumn or winter it is ‘game over’. In summer, it might be possible to fix the colony, if caught early enough, by removing the old queen and supplying a comb of brood from which a new queen can be raised.

Drone laying workers

By the time this situation occurs the workers will be too old to create a new, well-fed queen. Any attempt to save the colony is probably a waste of time and resources.

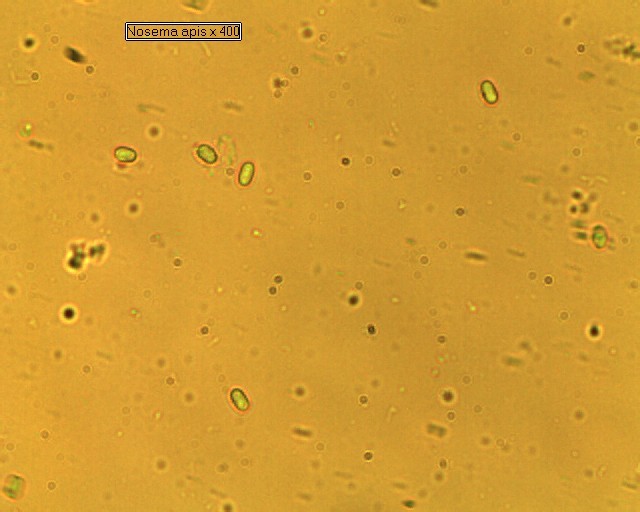

Nosema

Evidence of Nosema at hive entrance

Nosema apis spores *

Classic signs of Nosema are bee poo on the front of the hive and possibly dead bees on the ground in front of the hive. Best to confirm your diagnosis with a microscopic examination of the bee poo. Feeding a protein source as well as sugar syrup may help them survive.

Varroa

Varroa damage *

Varroa and DWV damage *

Varroa is still with us and still killing colonies! The image shows typical varroa damage, emerging brood with extended mouthparts and partially removed cappings. Deformed wing virus (DWV) is visible in the second image.

Images marked * Courtesy The Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), Crown Copyright. More images and advice at BeeBase.

Hive knocked over

Always strap hives in winter. Even if the hive is knocked over the bees will survive, provided the hive parts are not scattered all over the apiary.

The ‘Knock Test’

To find out if your bees are still present, put your ear to the brood chamber and knock the hive. You should hear a momentary buzz.

Dealing with ‘Dead Outs’

You should remove the hive and tidy everything up. Clean and sterilise frames and scorch boxes so that swarms or robber bees do not enter possibly contaminated gear.

My Colony is Queenless

The priority here is to make absolutely sure there is no existing queen before trying to introduce a new queen. These are Clare and Martin’s pointers to queenlessness:

- Can’t find the queen

- No eggs (or larvae or sealed brood)

- Bees are disorganised and buzzy

- There is a queenless ‘roar’

- Reduced activity at the entrance

- Colony has become a drone layer

- No eggs but emergency queen cells present

The reason you need to be sure of queenlessness is because, if there is already one in the hive, (it could be a dud, or an unmated virgin, or a drone layer), the workers will kill your attempted introduction of a new queen. A good way to check this is to put a queen from another hive in a cage and place this on the brood frames. If the workers ignore the cage they already have a queen. If they crawl all over the cage and try to feed her it is fairly certain they are desperate for a new queen.

Maybe there is a queen, but you have not found her yet. If there is no brood, she may not have started to lay yet, and sometimes queens just stop laying for a while e.g. when the main flow has finished. Or she could have got above the queen excluder. Sometimes, a queen returning from a mating flight will miss the entrance and end up under the hive.

Alternatively, she could have left with a swarm. Look for characteristic clusters in nearby trees, lots of queen cells in the hive, no eggs in the brood area and possibly depleted numbers of bees. Additional reasons for queenlesssness are beekeeper error (queen squashed by accident), a supercedure that didn’t succeed, or maybe she just died of old age at a time of year when she could not be replaced.

When you have ascertained there is no viable queen in your colony, it is time to decide what to do. Three approaches:

- Where there are queen cells present, ask the question ‘Was the colony strong enough to produce a good, well-fed queen? Remember that the existing workers are getting older and less able to perform house-bee duties. Leave only one queen cell. Martin’s tip for selecting that one cell is to observe which queen cell the workers are oriented to. That one will probably be your best bet.

- Where there are definitely no queen cells you may wish to introduce a new queen cell (one of your own perhaps). In this case you will need to prepare the colony for queen introduction. Obviously, make sure there is no possibility for the bees to raise their own queen. Consider introducing a protected queen cell, either in a special cage or the simpler aluminium foil wrap, leaving the tip uncovered.

- To speed up the recovery of your queenless colony you may wish to introduce a new queen rather than a queen cell. The safest way is to create a 3 frame nuc with no viable eggs or larvae, then introduce the new queen to that. When she is established and laying, then use the newspaper method to combine the nuc with your original hive.

How long must I wait for a ripe queen cell to become a laying queen?

Absolute minimum would be around 12 days, but could be up to 35-40 days before you need to worry.

How many hives are too many hives?

There are no set rules, but there are some considerations we should all engage with.

- If your beekeeping becomes a chore, it is probably time to reduce your colonies.

- The honeybee colony has evolved to produce several cast swarms, so queen cells should be reduced to one. If you have multiple swarms, you can combine them all in one box.

- The environment your bees are in has a limited capacity to provide sufficient nectar and pollen, so best not to overcrowd your apiary. In the wild, a swarm will usually look for a new home more than 300m away from their parent colony.

Our thanks to Clare and Martin for a stimulating and informative talk, and we hope you enjoyed the tea and cakes.